ROY EVANS’ pupils narrow somewhat, although not in a hostile way, writes SIMON HUGHES. There is a sense of acceptance. He appreciates the subject matter is near, the one he has discussed during every interview since leaving Liverpool in 1998 following 35 years’ service to a club where he filled nearly every staff role.

ROY EVANS’ pupils narrow somewhat, although not in a hostile way, writes SIMON HUGHES. There is a sense of acceptance. He appreciates the subject matter is near, the one he has discussed during every interview since leaving Liverpool in 1998 following 35 years’ service to a club where he filled nearly every staff role.

I have been leading to this point. We have spoken about his childhood, his brief playing career, becoming a successful reserve-team manager, first-team coach-cum-physiotherapist, then Graeme Souness’s assistant. And now here we are, arriving at the inevitable, discussing a term that ended up defining his entire managerial career, possibly his life — the Spice Boys. “I knew we’d get there eventually,” he shrugs, taking a quick sip of his coffee before answering the question I’d just posed to him: did you feel let down by the players in any way? “Listen,” he begins matter-of-factly, sinking into the couch behind him. “You can call them Spice Boys or whatever you want, but when they played football matches, they wanted to win.”

A pause. More coffee.

“The attitude was always good when it came to the game. They had a great ability. Did we fulfil our promise? Probably not. On our day we were as good as anybody but our day didn’t come quite often enough. We got caught out too many times believing we could attack any team and outscore them.

“It was my choice to go that way. Attacking was our strength. Just look at the players we had. But you could also say it was our downfall. The outside stuff — when players went home — it was irrelevant.”

There is a curious mix of positivity and stoicism in Evans’ tone. He is clearly proud of managing Liverpool. Yet there is pain. Surely it annoys him, being asked repeatedly about those white suits worn at the 1996 FA Cup final before losing to Manchester United, with people believing it was symptomatic of the fact he was too nice to impose the discipline supposedly required to achieve success?

“I don’t see what the problem is with being a nice guy,” he responds swiftly. “I hope I am a nice guy. Other Liverpool managers before me were nice guys too. We tried to do things in the right way.”

Evans insists that there were situations when he couldn’t be, as he puts it, ‘Mr Friendly’. “Like when you’re standing there in front of 20 lads doing a team talk and someone starts giggling at the back, you have to be on it. When Don Hutchison started sniggering about something I’d said in front of the group, I ripped straight into him and the room fell quiet pretty quickly.

“You don’t have to like all of your players as people. You don’t even have to like all the staff you work with. But you have to make sure you have a relationship that works for the benefit of the group and the club. I was never one to stay angry. I brushed things off. I got on with things as normal after telling someone off. If there was a confrontation, I’d get over it quickly. Maybe some people saw that as me not being tough enough. Any manager will tell you, though, you can’t afford to hold grudges.”

He did not set out to be Liverpool’s manager anyway. Evans was no careerist. “I never wanted to be a coach, you really must understand that,” he explains. “I’d played a few games for Liverpool’s first team. I was 26. Bill Shankly had just retired and Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan approached me, asking whether I wanted to join the staff. ‘No way,’ I told them. I felt like I had plenty of games left.

“It became a bit of a myth that I had problems with injuries. I just wasn’t playing much because there were better options than me. In the end, Bob and Joe nagged for a while. They wanted me to take charge of the reserve team. ‘Why not take the chance?’ they kept asking. Tommy Smith was my best mate and best man at my wedding. He thought it was a good idea. So, after a lot of persuasion, I took it.

“Individual ambition among the coaching staff wasn’t particularly encouraged at Liverpool. There wasn’t any clear policy but you had a job and you did it. You didn’t look for the next guy’s job. If it came along, great. As time went on, I progressed. I became first-team coach, running on to the pitch with the sponge. Then I became assistant under Graeme [Souness]. When Graeme left, I was offered the [manager’s] job by the chairman at his house and I’d accepted it within an hour. It was all done in a day. I didn’t ask him how much the contract was worth or anything like that. Until that point, I’d never really considered it — being a manager. But I realised that I had a lot of experience, having worked under some great people. I figured it was my turn.”

Anfield had been his place of work for his entire professional life. He knew of little else. Between 1994 and 1998, he was the gatekeeper to all Liverpool’s hopes and dreams. Yet he is the man on the street with the ordinary-sounding name: Roy Evans. His marriage to Mary is halfway through its fifth decade. He left school without many qualifications. He says he doesn’t read books. He wears a tank-top and when he meets me he is rattling a set of keys like an off-duty caretaker. He is short and has cropped silver hair. He speaks in old-school Scouse: fast, hushed and often from the side of his mouth. You have to listen closely.

You could imagine him being the voice of reason in a lively football debate among punters at a darkened Dock Road tavern. Evans was originally appointed after Souness’s departure because Liverpool wanted to return to tradition. Evans considered himself as the ‘spokesman’ for Liverpool. Yet he was the one with everything to lose. When Evans took charge, only four years had passed since Liverpool’s last title. During his era, Liverpool were expected to be champions. They never were. Whenever Liverpool lost, the radio football phone-ins were clogged with listeners wanting to be listened to, talking about Evans’ position. Even when Liverpool drew or conceded a soft goal, there was a jam, the same people taking part, the same topics being discussed.

“Of course I’d hear them,” Evans says. “It’s very nice to get patted on the back. But most of the time as manager you’re taking stick. The good times don’t last very long. I’m always saying to people, ‘Hey, you might have an opinion but yours will never get put to the test.’ My opinion was being tested week-in, week-out; day-in, day-out.

“I’d supported Liverpool since the 1950s. I can remember when we were in the Second Division and struggling to get out of it. By the 1990s, there was a generation of supporters who’d been brought up on nothing but success. They wanted more of a say about what was going on. It might have been better if some of them had gone through a period of lean years. Then they’d understand what football is all about.”

Evans felt “an unbelievable pressure” of expectancy. Before him, Souness underwent a triple heart bypass. Bill Shankly died a sad and lonely man. Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan were unable to communicate to a wider audience and their successes made them even more nervous as speakers in the public arena. Kenny Dalglish admits he lost the ability to make decisions, later referencing in the first of several autobiographies a Shankly quote about a “lifetime of dedication” that “follows you home, follows you everywhere, and eats into your family life”.

Evans felt “an unbelievable pressure” of expectancy. Before him, Souness underwent a triple heart bypass. Bill Shankly died a sad and lonely man. Bob Paisley and Joe Fagan were unable to communicate to a wider audience and their successes made them even more nervous as speakers in the public arena. Kenny Dalglish admits he lost the ability to make decisions, later referencing in the first of several autobiographies a Shankly quote about a “lifetime of dedication” that “follows you home, follows you everywhere, and eats into your family life”.

Evans had been there for all of this. He was aware that being in charge of Liverpool came at a price. “I’m not sure that being a fan of the team you manage is necessarily a good thing,” he continues. “The doubts start the first time you get beaten. Only then do you realise what it means to so many people. You take the job, you say to yourself, ‘This is great — I’m managing Liverpool, the club I love, I know what this is about.’ But your heart rules your head. When you’re winning, life is rosy. When you lose, you realise how it can spoil a person’s day or week. It’s your feelings multiplied by 45,000 people at Anfield and those watching it on TV or listening on the radio. Liverpool is a club where you’ve got people waiting outside the training ground every single day. It’s not just kids, either. Fellas are there; they’re 20, 25, 35 or 40 years old. These people, they’re dependent on the result. It breaks their hearts when that doesn’t happen.

“That’s the difficult part. It hit me hard. You obviously need to have some sort of social life yourself. If you haven’t seen the wife all week, which was regularly the case, you’d go out for a meal on a Saturday night. It wasn’t nice if we’d lost. You felt like you’d let people down, there was a horrible feeling deep in your stomach. You didn’t want to be there. There was a level of embarrassment to it. Whenever you were beaten, it felt like there were no positives.

“I’m certain it hurts even more when you support the team you’re managing. It hits you two ways. Like any person, you take a pride in your job but it also hits you as a fan. It’s a double whammy. The key is not to show any of this to the players.”

It took him weeks to even think about watching a replay of the 1996 cup final. “Would you want to watch that first half again? Fuckin’ hell…” he pauses again. “But look, I came through the system, I’m probably the luckiest Liverpudlian ever, to be able to be there as a kid, a player, do every job and end up as the manager. I don’t think there will be another person who does that.”

Evans was born on October 4, 1948 and grew up three miles north of Anfield in Bootle, an area that had suffered serious bombing during the Second World War due to its close proximity to Canada Dock and Gladstone Dock, a pair of significantly sized maritime landmarks that provided cargo links with North America and West Africa.

Although Bootle is now virtually politically impregnable as one of the safest Labour seats in the country, at the start of the 20th century it had been a Conservative haven — a reasonably prosperous suburb of boulevards and towering Victorian houses owned by rich merchants who once elected Andrew Bonar Law as their MP, a future Tory Prime Minister.

After 1945, with the borough in need of rebuilding, those with money moved up the Mersey coastline to neighbouring Crosby or further to Blundellsands, Formby and then Ainsdale, Birkdale or Southport. Bootle took on a new identity. On the flattened land, new cheaper homes were built. Out towards Netherton, an inland tangle of featureless council estates, the Evans family lived on Masefield Crescent before moving to a terraced house close to the large Mons Public House in the mid fifties.

After 1945, with the borough in need of rebuilding, those with money moved up the Mersey coastline to neighbouring Crosby or further to Blundellsands, Formby and then Ainsdale, Birkdale or Southport. Bootle took on a new identity. On the flattened land, new cheaper homes were built. Out towards Netherton, an inland tangle of featureless council estates, the Evans family lived on Masefield Crescent before moving to a terraced house close to the large Mons Public House in the mid fifties.

The Evanses were workers, his mother for English Electric and his father, Bill, on the production line at the nearby Dunlop rubber factory on Rice Lane in Walton. Bill’s income was supplemented through football. After playing for Liverpool’s youth team before the war, he signed for Cardiff City. It led to a decade playing semi-professionally for a series of clubs in the Welsh Football League.

“Every Saturday, he’d be driving a few hours for a decent wage, £8 a week or £10 a week,” Roy says. “It was a decent standard; there were no mugs. The teams were full of Liverpudlians with the same idea. Even when he stopped earning, he continued playing in the Business Houses League across Merseyside. It meant my mum saw more of my games than my dad did, because he’d be out earning money.”

On Sunday mornings, Evans remembers seeing matches at a public playing field over the road from his house. “Sport was on my doorstep. You could see all the men getting angry. You’d have fisticuffs. But at the end of the game, they’d shake hands.”

His football education was furthered by watching Liverpool and Everton play home matches on alternate weekends. At Anfield, he stood in the boys’ pen. This was an area of the Kop reserved for pimply faced urchins, where other “extras from Oliver Twist”, as an observer from the time once described them, would shriek swear words all afternoon. Evans recalls the sense of achievement when he invaded the pitch to celebrate Liverpool’s promotion from the old Second Division in 1962 as a 13 year old. By then, he’d already become the best player successively at St Robert Bellarmine primary school and then St George of England secondary school. “I always seemed to be two years younger than the lads I was playing with and against.”

Progress was marked by selection for Bootle Schoolboys, Lancashire Schoolboys and then England Schoolboys. Offers came to join Chelsea and Wolverhampton Wanderers. Yet it was Everton who were most determined. “The scout was on my doorstep every Sunday morning.” Evans waited. Finally, Liverpool approached. Not for the last time, he went with his heart, even though it meant giving up cricket, a sport in which he again excelled, representing Lancashire. “I went to Shanks and asked if I could go on tour with them. It was just a simple ‘No. It’s football or nothing.’”

On Monday, March 16, 1970, Evans made his first-team debut in Liverpool’s 3-0 victory over Sheffield Wednesday at Anfield. A stand-in for Ian Ross at left-back, he kept his place when Ipswich Town were beaten the following weekend. But after a 1-0 defeat at West Ham United, that place was lost. Evans says he was plagued by a feeling that he was not quick enough for First Division football. “It had never been a problem when I was younger but suddenly I felt a couple of steps behind everyone else. In my mind, I knew what I wanted to do but my body wouldn’t really let me do it.”

Between August of the same year and December 1973, Evans played just four games before another chance came against Manchester United. Wearing the number 3 shirt, he kept George Best quiet during a 2-0 win. “At the final whistle, Besty came over and thanked me for not kicking him off the park.” Four days later, Evans played his last match, a 2-1 loss at Burnley. Alec Lindsay, virtually ever-present previously, returned to the side and six months later Evans was offered the post of reserve team trainer. He says those in the Boot Room had spotted his ability to “follow instructions and pass information on with a bit of enthusiasm”.

Between August of the same year and December 1973, Evans played just four games before another chance came against Manchester United. Wearing the number 3 shirt, he kept George Best quiet during a 2-0 win. “At the final whistle, Besty came over and thanked me for not kicking him off the park.” Four days later, Evans played his last match, a 2-1 loss at Burnley. Alec Lindsay, virtually ever-present previously, returned to the side and six months later Evans was offered the post of reserve team trainer. He says those in the Boot Room had spotted his ability to “follow instructions and pass information on with a bit of enthusiasm”.

Evans was hired by a group of five men with a combined age of 259. Bob Paisley, Liverpool’s new manager, was 55; his assistant Joe Fagan and head of youth development Tom Saunders were both 53. First-team trainer Reuben Bennett was nearly 59 — the same age as Bill Shankly when he retired a few months earlier — while Ronnie Moran, promoted from reserve- to first-team duties, was the youngest at 40 but had nearly a decade of coaching experience behind him already. Evans was just 26.

These were people who since 1959, when Evans was 11 years old, had helped take Liverpool from eighth position in the old Second Division to the cusp of European greatness, men old enough to claim a pension, avuncular types with so many creases on their foreheads it seemed as though their knitted hats had been tacked on. In normal circumstances, they would be travelling around Liverpool on reduced-rate bus passes, yet here they were at Melwood wearing Gola tracksuits, heavy black jumpers and muddied football boots, showing professional footballers half their age how it was done in five-a-side matches.

The Boot Room was a shabby space, 12 feet by 12 feet, that reeked of dubbin, liniment and sweaty boots. There were no windows. Almost-empty bottles of Glenfiddich stood on a few wall ledges and the floor space was taken up by crates of Guinness Export and cases of Harp lager that doubled up as chairs to complement the two real ones by the old wooden door. It was staff-only. Every day of the week, Paisley, Fagan, Moran, Bennett and Saunders would gather to discuss what had gone well in training and what had not. Any player found lurking outside suffered the wrath of Moran. After matches, the doors were opened and stars like musician Rod Stewart, opposition coaches and managers were invited in.

Although the premise was for “a cup of tea or a beer”, as Moran puts it, in the true spirit of Liverpool, kidology conversations were geared towards gathering information that might lead to another Liverpool victory some time in the future. Evans calls it “interrogation by feather duster”. Bill Shankly, who had his own office and other duties to attend to, rarely ventured into the Boot Room, only occasionally showing his face. In his absence, the other staff members would even gather for a debrief on a Sunday morning from 10 o’clock until 12, after those of a religious persuasion had been to Mass. Boots were washed and hung back on pegs — first team first and reserve team second. Kits were absent, however, having been transported home in wicker baskets after the match. The staff did not trust external laundrymen after several kits had been shrunk or gone missing. The responsibility was now shared between Evans and Moran, who passed the duty of washing shirts and shorts on alternate weekends to their wives, Mary and Joyce.

“Imagine being so young and being welcomed into a place that at the time was the place to be. It was like being invited on tour with the Beatles. But what made the Boot Room wasn’t the room itself; it was the people inside it — the clever minds. In reality, it was a pokey little space underneath the Main Stand, filled with cases of beer, bottles of whisky and boots.

“My biggest input initially was a Playboy calendar on the wall,” Evans laughs lightly. “People would send them through the post to us. If Liverpool ever lost, which wasn’t very often, Bob would look at the calendar, point at the pair of tits and go, ‘Those two up there could have done better today.’ Then, despite the defeat, we’d chuckle along with him.”

Although he took no notice of the comment at the time, Evans was earmarked more or less immediately as a future Liverpool manager by chairman John Smith. “We have not made an appointment for today but for the future,” he said. The grooming process was under way.

Although he took no notice of the comment at the time, Evans was earmarked more or less immediately as a future Liverpool manager by chairman John Smith. “We have not made an appointment for today but for the future,” he said. The grooming process was under way.

“Reserve-team matches were played on the same day as first-team matches. When the opportunities were there, like a European game, they’d tell me to come along. The message was always the same. I can hear Bob telling me now, ‘If you’ve got something to say, say it.’ For my first year, I thought, ‘Hang on a minute, I’m 26, I was a bit-part player at best not so long ago; what can I offer?’ So I asked them why. I went to Joe. ‘It’s nice you’re giving me the right to speak and have an opinion, but…’ Joe stopped me. ‘You might just see one thing we don’t, a little gem one day that we’ve all missed. If you think we’re wrong, tell us. And if we think you’re wrong, we’ll tell you. But never take offence if that happens. It’s only opinion.’

“With the reserves, I could do it my way. Bob, Joe and Ronnie would come to our games when they could and sit on the bench. They wouldn’t interfere. I was the one making the decisions, telling players off when it was necessary. It gave me tremendous confidence.” Evans was his own man. “The trick was to put your personality into it. I was never going to be a Ronnie Moran, someone whose work can’t be underestimated. He made sure everyone fell in line and gets called the sergeant-major, but he was much more than that. Joe was the glue. Bob wasn’t great at speaking in front of a crowd but everyone on the staff knew what he meant. Then I was the fella that put the arm around a few, hence the reputation as Mr Nice Guy. There was a great balance, all good people, nobody went after anyone else.

“I remember going to Man City once and we won convincingly. Joe was manager. Afterwards, we went into their Boot Room for a drink and one of their coaches comes in going, ‘Our manager picked the wrong team today.’ Joe looks at him and responds, ‘What are you telling us for? If you think that, go and tell the manager to his face, not us.’ That kind of thing never happened at Liverpool.

“When I was in charge [as manager], I’d discuss the team with the staff a few days before. ‘This is what I’m thinking of.’ Then we’d go round the table, each person offering their own ideas. But once I’d made the decision, I’d insist they backed me. You should never, as staff, go behind the manager’s back and try to be clever after the event. When you’re part of a coaching team, you back the fella in charge.”

Paisley won more trophies as Liverpool manager than Shankly. Yet without Shankly, Evans believes Liverpool would never have moved forward, offering Paisley the opportunities he exploited. Although Shankly was asked by Paisley not to turn up at Melwood following his retirement, with Paisley feeling undermined by players still referring to Shankly as “Boss”, Shankly’s influence at the club remained. “Really, the Liverpool way is Shanks’s way,” Evans says. “The man came and changed the whole outlook of the club. It was all about good players doing the simple things well. He wasn’t the greatest coach in the world. Joe, Bob and Ronnie took most of the training. Shanks would throw a little bit in. But he was the best manager, the best motivator.

“You certainly can’t coach a team to win. There is no manual that says: ‘This is how you win football matches.’ There are training techniques and tactics that can help you win. But the art of winning is something you can’t teach. Shanks was great at making people feel good and brilliant at making people feel awful as well. With one word, he could make you feel 10 foot tall or bury you deep into the ground. He was like an actor doing a job. I thought of him like I thought of John Wayne. Other days, he’d be like a mafia mob boss. He made it fun; he made it all about the ball. He also trusted players to make big decisions on the pitch. Above all, it was geared towards getting the result at the end of the week.”

Although Shankly was gone, his ideas helped Evans establish himself as reserve-team manager. For example, on Monday afternoons Shankly had instituted the tradition of six-a-side games, with the sides made up of two first-team players, two from the reserves and two juniors. “You’d get a 16 year old playing up front with Roger Hunt. Other weeks, it’d be Cally [Ian Callaghan] or Gerry Byrne. The interaction was great. If one of the senior players thought a youngster had a chance, they’d take them under their wing and push them forward to the management.

Although Shankly was gone, his ideas helped Evans establish himself as reserve-team manager. For example, on Monday afternoons Shankly had instituted the tradition of six-a-side games, with the sides made up of two first-team players, two from the reserves and two juniors. “You’d get a 16 year old playing up front with Roger Hunt. Other weeks, it’d be Cally [Ian Callaghan] or Gerry Byrne. The interaction was great. If one of the senior players thought a youngster had a chance, they’d take them under their wing and push them forward to the management.

“Being so young, sometimes I had to deal with players that were older than me, players that had been better at football. But the culture of the club was well established: if you didn’t play for the first team, you played for the reserves. It was the accepted norm. We also had a very strong team. We played winning football and aimed to win the reserve league every year. The more experienced lads knew, coming with us, they weren’t playing with a bunch of nuggets, because they’d already trained with us too. We really wanted it.

“Shanks had instilled the idea that the second-best team in Liverpool was the Liverpool reserves and not Everton. It resulted in reserve matches being seen as important. If a player wasn’t in the first team, his only way back was by playing well for the reserves. I think every player treated the reserve matches seriously. At the end of the day, they were pulling on the red shirt of Liverpool. It mattered.”

Evans admits that he did not have the “charisma” of Shankly, the “ruthlessness” of Paisley nor necessarily the tactical mind of Fagan. He believes his main strength was common sense. “I understood what a lot of the boys were going through, because a few years earlier I had been in the same position. Some of them needed delicate handling, so there were times when you’d put your arm round their shoulder and then other times when you needed to give them a bollocking.”

After the turbulent Souness regime, Liverpool needed a steady hand at the helm. The summer before his appointment as manager, Evans became assistant. The board were preparing for Souness’s departure. Having tampered with the hereditary line, Evans was a return to what the board once knew. It was never admitted publicly but, within, there was a hope that Evans could create a new Boot Room. Souness’s era had left Evans without any natural successors. With Moran becoming assistant, he approached Tottenham Hotspur’s Doug Livermore, an old teammate from the reserve days, and made him first-team coach. Livermore had left Anfield to coach Norwich, Spurs and the Welsh national team. Sammy Lee, another home-grown and hard-working disciple of the Liverpool way, was charged with managing the second string.

Evans also realised that there was a need for specialists. In the past, even the great goalkeepers like Ray Clemence did not have a coach directing them. Clemence always trained with the outfielders, improving his reading of the game so that he was able to sweep up behind the defence. For a short period at the start of the 1970s, Shankly allowed Tony Waiters, who had appeared as goalkeeper for Blackpool on more than 300 occasions, to work with Clemence and the defence. Yet Waiters — a clipboard-and-whistle type of a coach — clashed with the other staff and within a few months he’d left for Burnley. When Clemence later admitted to Shankly that he was a nervous goalkicker, Shankly’s response was to remove the flags at the top of the Kemlyn Road Stand. If there was no sign of wind, there was less to worry about.

Evans realised such a basic approach amounted to neglect of a crucial position. “Graeme toyed with the idea of getting someone in but Bruce [Grobbelaar] had been our first-choice goalkeeper for so long and he actually preferred training as an outfielder,” Evans says. With Grobbelaar on his way out of Liverpool and his successor David James needing guidance, Joe Corrigan, who’d played more than 600 times as Manchester City’s number one, was named goalkeeping coach.

The next move was to appoint a full-time physiotherapist. With Mark Leather’s arrival, there was an end to the running repair jobs carried out by a succession of unqualified coaches mid game. Regularly injured players had long been treated with suspicion at Liverpool. Shankly maintained his side were the fittest in the league, with pre-season geared towards building stamina and therefore preventing muscle tears. It was a difficult theory to argue against. Liverpool won the 1965-66 title using just 14 players all season. Anyone who suffered an injury was almost bullied into feeling better. “Otherwise you really were persona non grata,” Alan Hansen said. Leather’s recruitment meant that Moran could focus on drilling the first team in the Liverpool way rather than writing what Evans describes as “little scribbles” on an old ledger, charting training patterns.

The next move was to appoint a full-time physiotherapist. With Mark Leather’s arrival, there was an end to the running repair jobs carried out by a succession of unqualified coaches mid game. Regularly injured players had long been treated with suspicion at Liverpool. Shankly maintained his side were the fittest in the league, with pre-season geared towards building stamina and therefore preventing muscle tears. It was a difficult theory to argue against. Liverpool won the 1965-66 title using just 14 players all season. Anyone who suffered an injury was almost bullied into feeling better. “Otherwise you really were persona non grata,” Alan Hansen said. Leather’s recruitment meant that Moran could focus on drilling the first team in the Liverpool way rather than writing what Evans describes as “little scribbles” on an old ledger, charting training patterns.

Evans recognised that the squad was not up to previous standards. He admits advising Souness against making certain signings. But he also reaffirms, “Once the manager has made his decision you have to back him.” Evans believes Liverpool’s deterioration began before Souness’s arrival. “It wasn’t the best team around in 1991,” he says, explaining that it was understandable if Dalglish had lost his focus after the Hillsborough disaster. “Football did not seem to matter any more.” Evans regrets waiting six months before starting his own rebuilding process. “There had been so many changes under Graeme, I wanted things to settle down and give everyone a chance to prove themselves. Maybe that was the wrong thing to do, maybe it was a bit of naivety. If I had my time again, I probably would have got rid of people sooner, bringing others in; enabling us to hit the ground running the next season. In my mind, I knew what needed to happen.”

With Evans as coach of the reserves, Liverpool had won five successive Central League titles and numerous regional cups. It was no coincidence that when Evans succeeded Souness as manager in 1994, having achieved excellent results with young players, the average age of Liverpool’s first team dropped by three and a half years. Although given a debut by Souness, Robbie Fowler flourished, scoring nearly 120 goals in four seasons. Evans had first seen the forward as an 11 year old putting a hat-trick past his own son, Stephen, who was a goalkeeper, during a schoolboys’ game in Burscough.

“Afterwards, I checked that Liverpool had already signed him and fortunately we had,” Evans remembers, adding that he felt lucky to be walking into a job that would involve working with some of the most exciting players in the country. “They were all different: different lads with distinct personalities. Robbie was a natural finisher. Maybe he didn’t have great pace but upstairs he had it going on. Then Michael [Owen] came into the situation. Nobody could deal with his speed. It was unreal. He gets a lot of criticism now, Michael — a bit like Steve McManaman and Jamie Redknapp, who was on the same level as anyone else in the Premier League in terms of passing ability. But these players gave the club nearly a decade of service. Joining Man United wasn’t the best thing to do but please don’t forget how brilliant Michael was.”

Evans would have preferred to use experienced players. “But when the young boys are better already, you can’t ignore them. Really, you want the senior lads to be forcing the issue — like when I was reserve-team manager, giving Bob no excuse to change the side. “Robbie was regularly in the starting 11 at 18. A bit later, you had Michael [Owen] starting games at 16. I know Michael has since said that it would have been better for his career if he was in and out a bit more. But Michael, for instance, would never stop asking to play. He was desperate. And with good reason. You try to balance it the best you can. Whenever I left Robbie or Michael out, they went crazy. They’d be knocking on my door and stopping me before training. That’s what made them top players. They were as keen as mustard. They wanted to play every game. I want players like that — not ones that didn’t seem bothered. There were a few of them about.”

Evans does not name names. But it is clear who he is referring to. Julian Dicks was the first to go: too fat and too slow. Then Torben Piechnik: just not good enough; Don Hutchison: too much trouble; Bruce Grobbelaar, Ronnie Whelan and Steve Nicol. In getting rid of the last three, it shows Evans was prepared to remove the old guard if he felt they were past it.

In his early years as reserve-team coach, Evans had worked closely with Fagan. Later, he spent more time with Moran. He says both had a knack of being able to pass on their knowledge without being overbearing — to teach a player to take on his responsibilities with confidence but to be true to his own personality. Their example of a more hands-off style led Evans to take a step back from coaching during his time as manager. “It was a bit of advice every now and then. I’m a great believer in encouragement. I hear people saying that Fergie liked throwing cups but he probably only did that once every blue moon to shake things up. You get more out of people in any job in any walk of life if you say, ‘Hey, good job, you did well today.’ You have to treat people fairly and as human beings first. On the flip side of that, when things aren’t right you have to let players know too. You have to go for them no matter how important they are to the team. It doesn’t matter if you’re Kenny or a young lad, you have to meet the level. If you let a bad performance slip and say nothing, it’s an unhealthy precedent.”

What infuriated Evans most was a player being unable to make a decision on the pitch. He’d rather someone had the courage to make a mistake and even someone who was then prepared to argue with him about it. “I expected the team to win every week but if they didn’t have an opinion about how the game should be played, then we were the daft ones, asking for the impossible.”

What infuriated Evans most was a player being unable to make a decision on the pitch. He’d rather someone had the courage to make a mistake and even someone who was then prepared to argue with him about it. “I expected the team to win every week but if they didn’t have an opinion about how the game should be played, then we were the daft ones, asking for the impossible.”

In training, Evans kept things simple — the Liverpool way. “Players need to enjoy what they’re doing in the long term. OK, in the short term there would be sacrifices in terms of fitness but you have to look forward to your work. Usually one unit of a training session would involve running and the rest would be with the ball. Sessions would be longer earlier in the week then shorter but more intense as you got closer to the match. The emphasis was always on the ball. We’d mix the rules up.

“The most important thing was to get a good tempo. There’s nothing worse than watching a game where everything is slow. If you play passing football at speed, it frightens the opposition. You can’t play against it. So the intensity of training was important. I wanted it to be intense, so the players didn’t have to flick a switch on the Saturday to get it right.

“If you enjoy yourself, you play well. Now, kids see a lot of the antics that go on. I ask them why they want to become a footballer. It scares me how many say, ‘Big car.’ I’ll tell them it’s the wrong answer. Fewer are saying it’s because they love football. Those that do are the ones you want. They’ll go further. For me, life isn’t about material things. It has always been about enjoyment.”

He concedes that maybe the players were “too free” to make their own decisions in an era where wages meant any “material thing” was available to them by outlaying only a small percentage of their weekly wage. These young footballers were different to the ones Evans had managed before. In an interview with Goal magazine in 1997, Evans gave some insight into the mindset at the time: “Week in, week out, our team talk is, ‘It’s great when you’ve got a talent but the most important thing is how the team plays and how you play for the team.’ Trying to get that into their minds [is tough], because the younger ones are all a bit Roy of the Rovers. Someone like Jason McAteer is always playing up to the crowd, and sometimes it distracts him. Yeah, he’s Liverpool daft but he’s got to concentrate on the game.”

Undeniably, however, there were distractions. Due to the influx of television and revenue streams for the newly revamped and globally marketed Premier League, footballers were earning more money than ever. Lifestyles were being portrayed as more significant than jobs. Look back through the autobiographies of players from the time and many of them read like guides to the London club scene. In his, Dominic Matteo — not even one of the stars — admits he thought nothing of following an all-night drinking session with a 10am champagne breakfast, or waterskiing across Lake Windermere while still drunk.

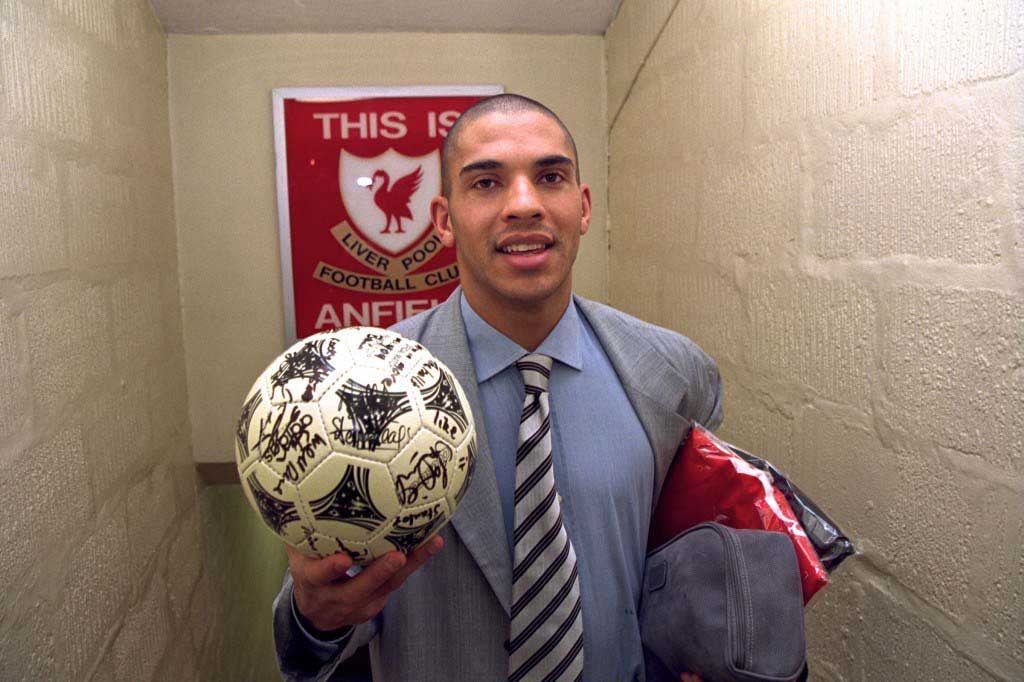

On becoming Liverpool’s most expensive player, Stan Collymore recalls being invited to Liverpool’s end-of-season do, meeting up in a London hotel near Lord’s Cricket Ground and walking into the room of a new teammate without knocking only to find him being treated to oral sex by not one but two mystery blondes. This was before the night had even started. He considers it a moment that summed up the attitude of the players at the time: partying before there was anything to party about.

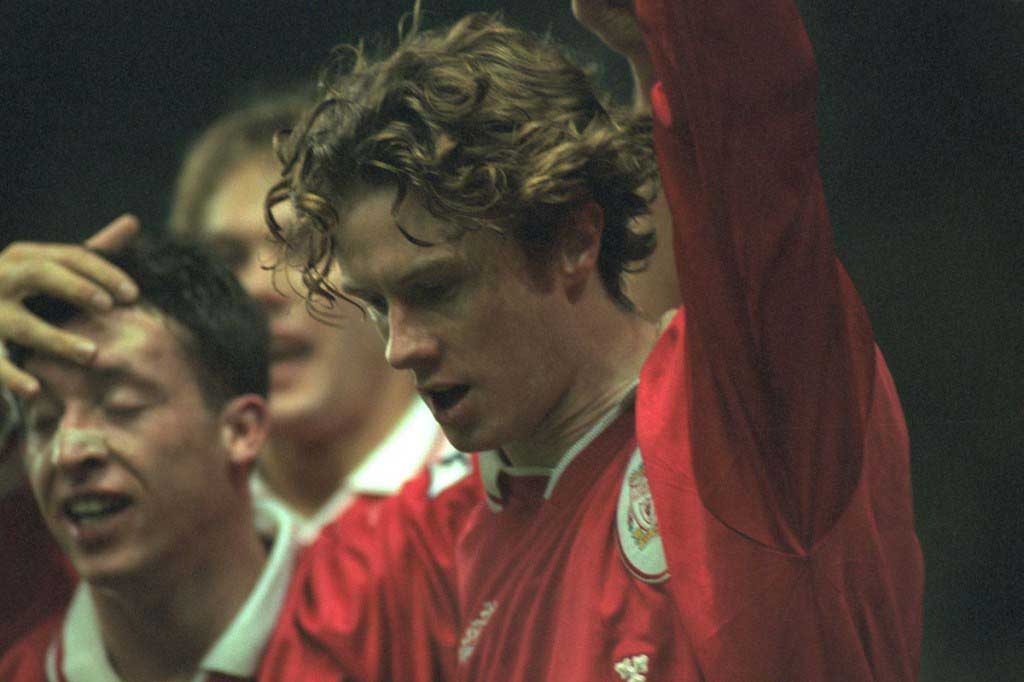

Managing these players was Evans, a man who blushes at the racy recollection of placing a Playboy calendar on the Boot Room wall. The Spice Boys label had not been invented when Evans won his only trophy as Liverpool manager in April 1995, beating Bolton Wanderers in the Coca-Cola Cup final 2-1 at Wembley largely thanks to an inspired performance by Steve McManaman. Progress was marked by a final league placing of fourth, a jump of four positions from the previous season.

Managing these players was Evans, a man who blushes at the racy recollection of placing a Playboy calendar on the Boot Room wall. The Spice Boys label had not been invented when Evans won his only trophy as Liverpool manager in April 1995, beating Bolton Wanderers in the Coca-Cola Cup final 2-1 at Wembley largely thanks to an inspired performance by Steve McManaman. Progress was marked by a final league placing of fourth, a jump of four positions from the previous season.

A year later, Liverpool finished third and memorably beat Newcastle United 4-3. It was the type of spectacle that Rupert Murdoch must have dreamed of televising when Sky started pumping money into the game. Liverpool’s football was sometimes breathtaking, with Fowler, Collymore and McManaman as a three-pronged attack, capable of scoring at any moment. Yet while this was happening, the players were being written about for their off-field antics. Jamie Redknapp married a pop star from Eternal. He and David James were on the front of magazines and involved in modelling for Armani. The photogenic duo jetted to Milan for catwalk shows and fashion shoots. Jason McAteer was the first footballer since Kevin Keegan to appear in a hair shampoo advert. His work with Wash & Go led to an appearance in the Top Man catalogue.

It might seem a normal thing for footballers now but this was a brave new world. Fowler and McManaman gave interviews to raunchy magazines like Loaded, where their faces appeared under such headlines as “BIRDS, BOOZE AND BMWs”. In February 1996, the pair were invited to the Brit Award music ceremony by McManaman’s agent, Simon Fuller, who also represented the Spice Girls. Surrounded by magnums and balthazars, Fowler was pictured with Emma Bunton, perhaps the most understated of the pop group. Even though Fowler claims Bunton was just a friend, the Daily Mail was the first on to the supposed non-story, labelling Fowler, McManaman and the rest of the players featuring regularly in the newspaper’s gossip columns as the “Spice Boys”.

Evans admits he was not prepared for any of this. Previously, Liverpool’s footballers had drunk themselves silly, gotten in fights and even ended up in prison. But, Jan Mølby aside, it had never affected the actual football: the appearances; the performances; the results. Evans admits that some of their “behaviour” was “a bit daft”. But he remains adamant that in the 1990s, the focus was always present when it came to matches.

“Football was changing and I chose to embrace it freely rather than take a tight rein,” he says. “They were young lads; Christ, they were young lads with a life to live. I wanted them to selfgovern and that involved the staff too. I didn’t want to hear about every single little indiscretion. If someone comes in five minutes late for the first time, I didn’t want to deal with it, even hear about it. I had bigger things to do. I trusted the staff to deal with it, dole out the discipline. Give them a bollocking and then move on. But, hey, if it happened time and time again then I wanted to know, of course.”

Self-governance had always been one of the Liverpool squad’s greatest strengths. There was a rank and file. Any player had to work his way up the chain. Barely a few months after first signing, Ian Rush considered moving to Crystal Palace due to a lack of first-team chances as well as the remorseless nature of verbal stick that came his way for speaking in a Welsh accent and wearing the wrong clothes. He was persuaded not to leave by Joe Fagan.

In the 1990s, Rush stood as Liverpool’s all-time leading goalscorer. By traditional Liverpool standards, the responsibility was on him and others like John Barnes and Mark Wright to pull their juniors into line if necessary. That they did not appear to might be considered a neglect of duty, although Evans does not see it the same way. “First and foremost those boys were there to do their own job,” he says firmly. “They wouldn’t have been there if I hadn’t felt they were capable of that. In a team situation, they tried to help the younger lads as much as they could. But the lads have got to listen too. It’s not as simple as saying, ‘Hey, you, control that.’

“The lads are who they are because they’ve got personality. You try not to quash that. I didn’t want robots. Sometimes I see the players in modern football and I want to hide behind the couch. You want personalities, people who are streetwise. But you also want people who are accountable — people who will admit when they’re wrong. I have no regrets at all about the way we went about our business. The only regret I have is that we never won the league.”

Evans believed the signing of Collymore for £8.5million from Nottingham Forest had the potential to capture the title for Liverpool. Six months earlier, Andy Cole had moved from Newcastle to Manchester United for a British record. The Collymore deal suggested one of two things: a) Liverpool were capable of competing with their greatest rivals in the transfer market at least, or b) Liverpool had panicked and felt it necessary to respond.

Had Frank Clark, Nottingham Forest’s manager, replied to Alex Ferguson’s telephone call quicker than Kevin Keegan’s — who had fallen out with Cole at Newcastle — there is a chance Collymore could have ended up at Old Trafford and Cole at Anfield. “We liked Cole,” Evans says. “We realised Rushy was nearing the end and we needed to find a replacement. We eventually got Stan but it was nothing to do with United spending money. I felt we really needed him.”

Collymore was 24 and still a few years away from his prime. His path towards Liverpool had not been easy. He was brought up by his single-parent white mother as the only black kid in a ferociously Caucasian working-class area of southern Staffordshire. Aged 18, he’d asked to be released from Walsall because he didn’t like the pugnacious coach Ray Train — a person he still blames for his aversion to training. Soon, despite scoring 18 goals in 20 youth-team games, he was given the boot by Wolverhampton Wanderers for an inconsistent attendance record. Collymore then found a home at Stafford Rangers in the GM Vauxhall Conference, where John Griffin, Steve Coppell’s chief scout at Crystal Palace, remembers seeing him for the first time after initially travelling north to check out a goalkeeper. “The keeper didn’t impress me but the 6 ft 2 ins lad built like a brick outhouse playing up front certainly did,” Griffin told the Mirror in 1997.

Collymore was substituted at half-time due to an injury but by then Griffin had seen enough. “I went back to Palace and told Steve I had just seen the best non-league player ever. He had two great feet, super skill and great strength. I couldn’t find a fault.” Palace had taken Ian Wright from park football and the plan was to eventually replace him with Collymore. Yet Collymore never felt a sense of belonging at Selhurst Park, where the Palace squad was split equally between black and white players and he was the only one from a mixed-race background.

At Southend United, first-team opportunities were there straight away and in the 1992-93 season Collymore scored 15 times to keep the seaside town club in the old Division Two. Those feats earned him a move back to the Midlands with Forest and over the next two campaigns his development was marked by another 41 goals. Forest, meanwhile, won promotion before finishing a place above Liverpool in the Premier League during their first campaign back in the top flight.

Evans claims Collymore’s ability was equal to that of Ronaldo, who, having been part of a Brazilian World Cup-winning squad, had finished as the top goalscorer in Holland during his first season at PSV Eindhoven after moving from Cruzeiro. “On the face of it, there wasn’t much of a difference [between the players],” Evans says. “They both had power, pace, skill and a great finishing ability. I’d considered Ronaldo, just as I’d considered a lot of players at home and abroad. But it boiled down to Stan being English and knowing the demands of the country and the Premier League.”

For the first 18 months, Collymore was successful without being prolific, developing an understanding on the pitch with Fowler, be it an understanding that did not extend off it. Collymore tells a story where he and Fowler argue in their first game together, a 5-0 friendly defeat by Ajax. It ends with Fowler telling Collymore to “fuck off”. After that, Collymore states he chose never to speak to Fowler again, perhaps illustrating what a sensitive and complex individual he was and probably still is: the type who would have either had all of his insecurities exposed and then flourished in his earliest days as a Liverpool player under the old dressing-room regime based on one-upmanship; or simply not have fitted in and gone elsewhere sooner rather than later.

Evans’ explanation is rather more superficial than that, suggesting Collymore had an ego. “Stan had always been the big fish in the small pond elsewhere. When he came to Liverpool, he was just another player. After 18 months, I hoped he’d get his head around it. It was a waste of his talent, because he had loads.” Evans is more open about Collymore than he is about any of the other players that represented him. The striker has been scathing in his assessment of Evans too. In his autobiography, Collymore pins many of Liverpool’s failings on the manager of a club that he suggests was stuck in a time warp. At Forest, Collymore admits he was the focal point of the team. At Liverpool, he claims Evans used him improperly, asking him to drift wide and drop deeper. He insists that Liverpool clung on to its links with former glories.

He is critical of Rush and Barnes, stating that they were not worthy of their places but remained because nobody had the courage to tell them to go (Evans did, in fact, during the summer of 1997, just before Collymore’s own departure). He saw Melwood’s four wooden training boards as a metaphor. The boards were “rotting away” but, acting as monuments to a time when Liverpool ruled English football, they remained in use as well. Then there was the lack of discipline in the squad. Players could walk on to the training pitch eating toast and on one occasion after a quip, Fowler allegedly got Evans’ head in an arm-lock, messing his hair with the free hand. Collymore asks what would have happened if Gary Neville had tried something similar on Alex Ferguson.

Most significantly, perhaps, Collymore recalls how Ronnie Moran took to calling him “Fog in the Tunnel” because of the number of times he was either late or did not turn up for training. Collymore lived in Cannock, a one-and-a-half-hour drive down the M6 on a morning without traffic. It was a journey he made most days. Evans understood that, for a period, Collymore’s mother was not well. He was prepared to make allowances. But then the pattern continued.

He asked him to move to Merseyside on numerous occasions. The request was ignored. Collymore continued to be late. It is at this point that Evans suspects his own future began to unravel. Collymore was not the most popular player in the Liverpool squad anyway. Living far from Merseyside, he was not a regular on the social scene. He was not really one of the lads. Now Collymore wasn’t turning up for work while others were and resentment built up towards him for, as one member of the team puts it, “taking the piss”.

There is a feeling from Evans that he felt lumbered with Collymore. Because of his financial outlay, he had to be patient with him. But it prompted a spiral of problems. There are other stories: of players taking shortcuts at training and not taking the football seriously enough. It has been said that David James once missed a session for one of his Armani photo shoots, although James himself denies this. As for Collymore, he eventually found himself in the reserve team. “Stan was one of those who raised his nose,” Evans says. ‘I’m not doing that,’ Stan would say. But I’m not sitting having a go at Stan. I think we’d blame Stan for everything if we could.

“He wasn’t the only one with that attitude but he may have been the first. He argued that he didn’t sign for Liverpool to play in the reserves. I told him that we didn’t sign players to play in the reserves. I felt he needed to be sharper — match sharp. It would have helped him. I can’t understand why players complain about playing in the reserves. It was only for their benefit. It was never a punishment. You can’t punish someone by asking them to play a game of football. You punish someone by leaving them out altogether.

“Stan let himself down in the last six months, when I felt he lost his concentration. It’s sad because he was one of those guys you feel could have gone on to be a really great player. His ability was natural: pace, power, technique — everything. But for some reason, he started making things difficult for himself. The other players would ask where he was when he didn’t turn up. You can only make excuses for a short period of time. It starts causing problems within your camp. I’d like to sit down with him one day in private, now we’re both a bit older, and discuss what really went wrong.”

Under Evans, Liverpool were becoming predictable and relied too heavily on Steve McManaman. And when he was absent, there was criticism that Liverpool had five defenders and a huddle of midfielders who played too deep and passed too short, missing a vital link with the forwards and instead feeding the play to the overworked wing-backs. Evans wanted to sign either Jari Litmanen (who later joined Liverpool under Gérard Houllier) or Teddy Sheringham.

Under Evans, Liverpool were becoming predictable and relied too heavily on Steve McManaman. And when he was absent, there was criticism that Liverpool had five defenders and a huddle of midfielders who played too deep and passed too short, missing a vital link with the forwards and instead feeding the play to the overworked wing-backs. Evans wanted to sign either Jari Litmanen (who later joined Liverpool under Gérard Houllier) or Teddy Sheringham.

“The Finnish lad [Litmanen] was a very, very clever player. We had people who could score goals and needed a few more who could create chances. We were playing in a friendly against Everton and Peter Robinson flew out to Amsterdam to speak to him. Again, he wanted the Champions League and went to Barcelona instead. “We then looked towards Teddy. The deal was a long way down the line and I was confident of getting it signed. The only problem was that the board’s policy was to buy younger players. It always had been at Liverpool.

“Lots of other clubs were signing foreign players on the wrong side of their thirties. Teddy was 29. We were paying big money for him. Teddy really wanted to come; we’d chatted all about it. But the board pulled the plug. It frustrated me because he spent four years at United and helped them win everything before moving back to Spurs until he was in his late thirties. I realised Teddy was no angel off the pitch — he liked a drink and a night out. But he was one of those guys who knew when and where. I figured he’d guide the younger boys.”

Then there was an argument that Liverpool were a ball-winner short of a title-winning team. Evans believed that in the prevailing refereeing climate, tigerish tacklers were a liability, though he was eventually persuaded to sign Paul Ince from Inter Milan, a midfielder in the tough-man mould. “Paul was in the world-class category and few of those were available,” Evans says of the former Manchester United player. “He wasn’t just a competitor. He was a leader and could pass, otherwise he’d never have been a success in Italy. We played with wing-backs and Incey had been schooled in a 4-4-2 system. In the end, it was a formation that we decided to return to.”

A new breed of lithe, agile midfielders was emerging, epitomised by Patrik Berger, who became Evans’ first foreign outfield signing for £3.25 million from Borussia Dortmund in the aftermath of an impressive Euro 96 campaign with the Czech Republic. British players at other clubs claimed the presence of foreigners helped improve their own technical abilities. While Evans admired Alen Bokšic´, then of Juventus, and Fiorentina’s Gabriel Batistuta as well as AC Milan’s Marcel Desailly, he was not tempted to emulate a Ruud Gullit-type signing in the transfer market just for the sake of it. “I didn’t want to go and get someone just to put more bums on seats. We filled Anfield anyway. You saw Gullit and Vialli, they were both well into their thirties and cost a lot of money. How long did Chelsea get out of them? If the chance had come to sign an older player — maybe in his late twenties like Teddy — I would have done it. But I wasn’t someone who wanted to fill the place full of foreigners. I thought there was enough talent in this country at the time.”

Eric Cantona’s legendary status at Manchester United did not help. “OK, a lot of people did not like Cantona because he kicked a fan [at Crystal Palace in 1995] and got banned. But his supporters loved him. And so did the media. He was this foreign fella, different. Everyone wanted one like him. It didn’t mean players like that grew on trees.”

The distrust of foreign footballers harked back to Shankly and Liverpool’s peculiarly Celtic insularity. Yet Evans did not have a single Scot in his first-team squad, a far cry from the glory days when Hansen, Dalglish and Souness led the fight. Instead, Evans allowed John Barnes a significant influence, someone who translated his thoughts on to the field. “John had some interesting points to make. He was another coach on the pitch. He was desperate for the team to succeed and that was the thing we really had in common.”

There is certainly more of Paisley than Shankly in Evans. He uses that term again — “spokesman” — when I ask him whether he might have been more forceful with the players rather than continue the tradition of self-regulation. The cult of the manager has grown since his departure, with coaches like José Mourinho imposing their characters on the identity of a club, attempting to command respect.

There is certainly more of Paisley than Shankly in Evans. He uses that term again — “spokesman” — when I ask him whether he might have been more forceful with the players rather than continue the tradition of self-regulation. The cult of the manager has grown since his departure, with coaches like José Mourinho imposing their characters on the identity of a club, attempting to command respect.

“When the club you manage is high profile, that makes you high profile because you’re in the public eye on a regular basis. But as far as my own personality being bigger than the club, I don’t see the point in that. I was there as their spokesman, really. It’s only part of the job but if you’ve got one voice then there’s no mix-ups, and we tried to keep it that way.”

Evans could sense the demands in football were shifting. He was prepared to listen to whatever the board of directors suggested when he was called in for a meeting by chairman David Moores in the summer of 1998. “I agreed there was a need for something different. The game was turning very European. The idea was to bring someone in who knew more about that side of it. We spoke to John Toshack and several other people about the idea of appointing a director of football. We needed someone who could help build a bigger scouting base and improve the training ground. John rejected the opportunity because he wanted to be a number one, and I should have learnt from that.”

Evans believes Liverpool “ended up” with Gérard Houllier. “Arsène Wenger had revolutionised Arsenal, and France had just won the World Cup. It seemed like a sensible idea to get Houllier in as joint manager and work together. I let my heart rule my head. Deep down, I knew it wasn’t right. I still regret going along with the idea of the board meeting him a few days before I did. I was on holiday in Barbados.

“[When we did meet] on the football side, we got on. At the end of the meeting, it came to roles, responsibilities and titles. I said something about not having an ego and that I’d do whatever was better for the club. It was a massive mistake. I should have been sharper or brighter than that. I wasn’t strong enough to insist that he would only be a director of football. I should have said that under no circumstances can two men do the same job. The board should have known that too. It had been tried at other clubs and it hadn’t worked.

“At the end of the day, you can sit down with your best mate and talk about football and you don’t have the same opinions. There’s always going to be a clash. And that’s what happened.”

Evans says he and Houllier did not disagree over “big things”. ‘It was silly things, like what time the bus left — stuff that erodes the confidence in the squad. Gérard’s a cleverer man than I am, that’s for sure. I don’t hold any grudges against him. But he knew this was going to happen, although he later admitted he didn’t think it’d be so quick. He was quite happy to bide his time.

“I felt it was starting to get to the players. While I was still there, all of them still called me ‘Boss’. I picked the team — the final decision always fell to me. Most of the players were on my side when it got into a bit of a war towards the end. The lads who weren’t in the team were always going to go with Gérard. It was messy. Should I have stayed and fought it out? Because I was a supporter of the club, I realised somebody had to go. It was never going to be Gérard; it was going to be me. Regrets? Of course. About not being the guy that pushed himself forward.”

“I felt it was starting to get to the players. While I was still there, all of them still called me ‘Boss’. I picked the team — the final decision always fell to me. Most of the players were on my side when it got into a bit of a war towards the end. The lads who weren’t in the team were always going to go with Gérard. It was messy. Should I have stayed and fought it out? Because I was a supporter of the club, I realised somebody had to go. It was never going to be Gérard; it was going to be me. Regrets? Of course. About not being the guy that pushed himself forward.”

Evans did not find the separation easy. “You leave Liverpool and you’re bitter. I’d been there my entire working life. I had six to nine months when I wasn’t interested. I didn’t care whether Liverpool won or lost. The wife would tell me the result and I’d grumble and walk away. I realised I couldn’t live that way. It was ridiculous. So I decided to become a fan again. Why spend the rest of your life hating something that you loved for so long? It wasn’t healthy.”

Evans hoped another top job might come his way. But Liverpool took their time settling his contract, meaning he missed out on opportunities elsewhere. “It took a fair while to pay me off, which didn’t help in terms of going to another club,” he says. “I always believed I had the best job I was ever going to have at Liverpool. But my record stands up today against any English manager in the Premier League. Maybe it warranted another shot. Maybe because I didn’t have an agent and, again, maybe because I didn’t push certain issues as I should have done, I was out of the public eye.”

In the years that followed, Evans took roles at Swindon Town, Fulham and the Welsh FA. “They were always jobs for other people, doing favours as a coach or an assistant. Sometimes in life you have to be a selfish bastard and I wasn’t.” He despairs now at the state of management generally. “Everybody wants to move into the top job straight away. Top players feel like they should go into management at the same level. I’m not quite sure that’s the way to go. Management is very different to playing.

“Players have to serve some kind of an apprenticeship and so should managers. You have too many coaches in management positions. Sometimes I feel they try to dictate too much of what goes on during games. They want to kick every ball of every game. Shanks, Paisley and Fagan set the team up and made it clear what the intentions were. But at the end of the day, it’s about people making decisions on the pitch. That’s what footballers are paid to do.

“Coaching, to me, is about making little points, tweaks. If you played for Liverpool, you were expected to know what to do. But there was nothing wrong with giving bits of advice, offering the right guidance.”

He remains adamant that his approach at Liverpool was the right one. “I wanted players to be free to make their own decisions. There was trust. Maybe I gave a bit too much. If it goes wrong, the buck stops with the manager. But you can’t coach winning. Before my team went on the pitch, I’d finish the team talk with a simple message, ‘Enjoy yourself’. After that, they were away. I trusted them to do the business.”

You can buy MEN IN WHITE SUITS by Simon Hughes (RRP £18.99) for the special price of £16.99, including free UK + N Ireland P&P. Offer closes 30 June 2015. To order your copy please call 01206 255 800. Please quote ref: Hughes

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: David Rawcliffe-Propaganda & PA Images

He was the right man at the wrong time.

So, Sack him! Sack Gerrard! Sack Rodgers! Sack Mignolet! Sack Sterling! Sack Markovic! Sack Johnson! Sack Henderson! Sack Allen!

(Just having a laugh guessing what the comments will be!)

What a brilliant football man. What a class act. We were lucky to have him.

Tremendous chapter, just bought the book.

I’ve seen the book described as “bittersweet” elsewhere and this comes through strongly here. It’s consistently a story of unfulfilled potential and opportunities missed, and sadly someone will write exactly the same story about the noughties and now in a few years’ time.

The right man at the wrong time, that’s what Souness said. Maybe they were both right, if only we could go back in a time machine and swap them. I think it is telling when Roy mentions that he advised Graeme against certain signings, but once he had made up his mind he had to get behind the manager. I think we can guess which signings he meant(Ruddock, Dicks), as well a few others. Would Roy have taken on Cantona, would he have accepted a request from a young goalkeeper, who described himself as a Liverpool fan , Peter Schmeichel? We will never know now, but the turning down of Schmeichel, is particularly galling. He was asking for a trial, Brucie wasn’t going to go on forever, what did he have to lose? Another revelation was hearing how Roy wanted Teddy Sheringham, who really wanted to come great, what went wrong, well the board thought he was too old at 29. Well done guys, that really paid off didn’t it? With friends like that, who needs enemies? Ultimately, by the time Roy took over, the damage had already been done, after losing Mark Lawrenson in 1988 and with the end of Alan Hansen’s career in sight, Liverpool by 1991, would be without two of, if not the two finest central defenders the club had ever had, the signing of a class central defender should have been a top priority. Had they done so its likely, that Liverpool would still have been on their perch.