LIVERPOOL is a football city. Few could argue with the assertion, but what does that really mean, and how are Liverpool and its people different from, say, Manchester or Newcastle in their relationship with the game?

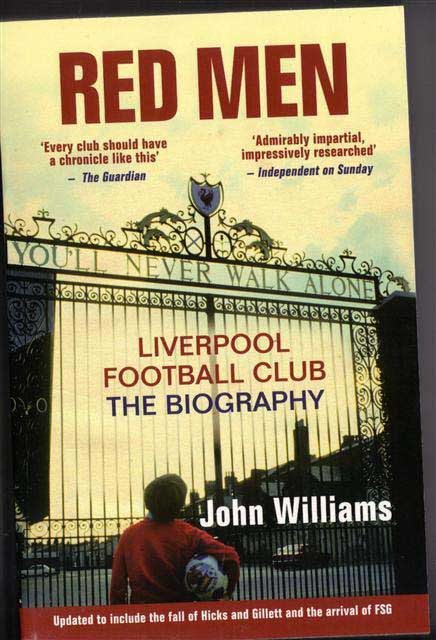

Sociologist John Williams is the author of Red Men, perhaps the definitive study of Liverpool FC’s early years and the club’s place in Liverpool society and the wider football sphere.

Drawing on huge amounts of primary source material, it’s a compelling account of how both Liverpool and Everton came to be embraced by the people of Liverpool, and of how the clubs’ relationships with the city, the media and one another have evolved over time.

John will be at the Bluecoat on Friday, October 14 for The Liverpool Way, a discussion of all this and more.

I spoke to him ahead of the event about the Reds, the fans and the great Alex Raisbeck.

What can we expect from the event at the Bluecoat?

I hope an evening when we can talk a little less (directly at least) about matters on the pitch and a bit more about the wider meaning of the game for the city and how the relationship between supporters, especially at Liverpool FC, and the club has evolved over time.

What can we learn from how the club, its fans and the city at large interact? How has this changed over the years and what are some of the factors which have influenced these relationships?

A number of things I think. Firstly that historically it was actually Everton that had ambitions to be a rather more open and ‘democratic’ club than Liverpool. John Houlding, Liverpool’s founder, had left Everton partly because he was not allowed to control things there in the way that he had wanted to do. Like many Victorian businessmen and politicians, Houlding was a mixture of patrician philanthropy and someone who saw the advantages of being involved in football for his own political and business ends. For many years after his death, the Liverpool board operated as a family led ‘closed shop’ and supporters had very few avenues they could use to question the club’s policies. At Everton things were rather more transparent.

I think Bill Shankly was a key figure in reasserting the importance of Liverpool fans to the club – he revived the idea (strong in the 1930s, but rather weaker later) that the club’s fans had ‘unique’ qualities.

In Red Men you illustrate vividly how Liverpool FC has quite rarely been a wholly or even mainly Liverpudlian enterprise. From the Team of the Macs through to Shankly, Paisley, Benitez and Dalglish the club has embraced outsiders. How far is this a product of the city’s own seafaring tradition and cosmopolitan influences?

I think the traditions of the city are an important factor here – but I also think the peculiar circumstances of the club’s origins are important. The new Liverpool had to find a robust team very quickly and John McKenna’s best contacts were among the ‘football professors’ in Scotland – where one might find fully formed professional players in the late-1890s. In the 1920s the Liverpool board was looking to rebuild quickly again after the title team began to dissolve and after a tour match to Anfield they saw the potential of the South African connection as a, typically penny-pinching, cheap option. But they were also well aware that recruiting from abroad would not be quite the problem it could have been in other, less cosmopolitan, cities.

It is also interesting how few southern-based English players Liverpool have hired in their history – we have always tended to look to the Celts, and to further afield, than to the English South.

It’s clear from reading the book that a huge amount of research went in to piecing together the club’s early history. How might the job of future football historians be altered by the advent of blanket TV coverage and the rise of the internet and social media?

history. How might the job of future football historians be altered by the advent of blanket TV coverage and the rise of the internet and social media?

Good question – Liverpool even produces a weekly printed magazine now, and there is so much more material from fans, which I think is the key change. Finding out what supporters thought about the game before WW2 is an extremely difficult task. Now it should be much easier. We tend to embroider player stories from the past because the footage is not available – maybe that will change, though somehow I doubt it. But in the end historians and researchers will still have to plough through material and make judgments about determining the important stuff from the rest. This aspect of sifting and interpretation is pretty much what we have to do now.

You talk about the cultural role of Liverpool Football Club in the city. How is this different from the role of Everton and football in general?

Right from the very early years of the sport – in 1906 when Everton won the FA Cup and Liverpool the league, and crowds here were larger than anywhere else – the city of Liverpool was identified as an early ‘capital’ of football. The city’s complex Celtic roots probably made the mythologies, artistry and emotions that swirl around the game rather more important for working people than perhaps they were elsewhere: with the possible exception of Glasgow.

Somehow, too, very early on the specific character of the Kop terrace – including its size and modernity – became a sort of lightning rod for debates in the city and beyond about knowledgeable and humorous fans in a way which never really happened at Everton. Then the unique relationship established between taciturn Irish keeper Elisha Scott and the Kop in the 1930s added to this mystique – Scott obviously identified with his supporters behind rather more than he did with his own team mates. After a period when both clubs struggled, John Moores spent heavily in the early 1960s to try to bolster the early ‘school of science’ myths about Everton. In response it was Bill Shankly who cleverly revived this idea about the ‘unique’ character and culture of Liverpool supporters at a time when local musical creativity was at a peak.

This deep-rooted idea about local exceptionalism was then cemented and extended by the media and when Liverpool supporters travelled around Europe in the 60s,70s and 80s. They saw themselves as something of a cultural elite – and they probably were. Everton’s recent response has been to champion a goading form of localism in the age of the global – which has added spice to local rivalries.

One of the key figures in the early part of Red Men is Alex Raisbeck. What drew you to him as a player and a character? Are there any parallels with players from the modern era?

The old style centre-half in the early playing formations was the pivot of the team – a key defender who was also expected to lead attacks. Raisbeck was obviously exceptional in this hugely testing role and he was instrumental in the two league titles of 1901 and 1906. There is some YouTube footage from a match at Newcastle which features Raisbeck – and his blonde head is a non-stop marker of energy and verve. He is clearly the crucial Liverpool player in the pre-WWI period – talented, brave and utterly committed to the cause. He is talked about in the press then rather as Steven Gerrard is often discussed today: as the defining figure who is likely to determine match outcomes and how the team performs. Many clubs have their defining players and Liverpool have had four or five over almost 120 years – Raisbeck, Scott, Liddell, Dalglish and possibly Gerrard from more recent years all fit the bill.

They are all ‘more’ than just footballers: they are in other ways emblematic of the club and its people. The Kop has recently started producing banners about great Liverpool players from the past – Liddell, Sir Roger etc – perhaps Red Men has played a part in this (I hope so). Raisbeck certainly deserves his place.

The relationship between Liverpool and its managers is a special one. Casual observers might assume this mutual bond began with Shankly, but does that tell the whole story?

There is something special about Liverpool and its managers – at no other club are they celebrated in quite the same way. Shankly had a native politics and a character that was made for Liverpool FC and the age of television, and he was also a crucial figure in redefining the relationship between the club and its fans. But his presence looms so large that other great Liverpool managers – Tom Watson in the early 1900s for example – are rather forgotten. At a time when the directors picked teams at most clubs, Watson was much more his own man at Liverpool and he built two great title winning sides and also got Liverpool to its first FA Cup final, in 1914. Watson was very widely lauded in the game as a great football man – someone who was devoted to football and who understood the importance of the sport and its people.

I hope Red Men has sparked more interest in the pre-Shankly era because this was my main motivation for writing it.

How much does the ownership of a club matter to its identity and relationship with fans?

When it goes wrong it matters a lot!

Interestingly given the politics of the city, for much of its history Liverpool FC was owned and run by local Tories – which rather suggests that ownership per se is actually relatively unimportant to most supporters. Who knew the club’s owners in the 1970s and 1980s? Before Shankly, the Liverpool board seems to have had a typically withering view of fans, but after him it was largely a case of directors stay in the background & speak only when spoken to.

But even in the 1970s Reds chairman John Smith was warning about the crazy economics of the sport and we are now in the position when we have to rely on global financiers pumping money into the club to maintain our position in Europe’s elite.

It is self evident that the top clubs need to get some control over players’ salaries to begin to change this around, but no-one seems to want to take a stand for fear of losing out. Players and managers matter to supporters more than anything else of course. But some authentic humility and pride from these billionaire owners is also important to fans – after all, the club is worth much more than money to those who follow it. Recently however too many fans seem to be saying: ‘We don’t care how devoted the current owners are – if they don’t have the money get them out and get someone (anyone) else in.’ I feel sorry for Kenwright on this score.

Let’s hope the new Liverpool owners understand that they have to have a much more intimate connection with the city and the fans than the last couple did. They are showing some promise on this score. And I really don’t think that most supporters want to ‘own’ their clubs beyond the psychological and emotional investment they make; but they do expect those who do to have at least a duty of care towards it.

@steve_graves

- The Liverpool Way is on between 5pm and 6.15pm on Friday, October 14 as part of the Bluecoat’s Chapter and Verse literature festival. Tickets, at £3 and £2 for concessions, and further information are available here.

Nice one, Steve and that’s a great little prezzie idea for my lad’s birthday coming soon. I’m off over to Amazon…..