THERE’S an argument in football that certain players belong at certain clubs. It’s a bold concept. I’m not sure but I think it’s something to do with a synchronicity of values, an alignment of shared characteristics. It’s not just about performances or goals or value for money. It’s a bit more abstract than that. It’s about embodying the things that you imagine your club represents. It’s when someone pulls on your team’s shirt and it fits. And if you want to see that as a gratuitous dig at bloated pound-passer, Neil Ruddock, that’s entirely up to you.

THERE’S an argument in football that certain players belong at certain clubs. It’s a bold concept. I’m not sure but I think it’s something to do with a synchronicity of values, an alignment of shared characteristics. It’s not just about performances or goals or value for money. It’s a bit more abstract than that. It’s about embodying the things that you imagine your club represents. It’s when someone pulls on your team’s shirt and it fits. And if you want to see that as a gratuitous dig at bloated pound-passer, Neil Ruddock, that’s entirely up to you.

There are numerous examples if you think about it. Alan Shearer, the democratically elected Geordie Messiah, and Newcastle United. He may have won a title with Blackburn but it’s hard to see him in anything other than the black and white stripes of his home-town club.

Cantona at Manchester United was more than just the catalyst for a period of sustained success, a dark cloud spreading across the football landscape like a harbinger of the worst kind of evil. With his pronounced cockiness and relative intellectualism (relative to, say, Lee Sharpe or a spoon), United fans saw him as a figurehead. He captured their imagination in a way nobody had since George Best.

And then there was Duncan-Big-Dunc Ferguson, whose narky, agricultural, unsophisticated, borderline psychotic approach to the game allowed literally all Evertonians a glimpse of their own deeply entrenched frailties, and yet they still loved him for it. Funny bunch.

Fifteen years ago this week, Liverpool signed Gary McAllister on a free transfer from Coventry City. A club and a player that were made for each other. It was difficult to see why it had taken so long.

McAllister played the game with a style and composure familiar to Liverpool supporters brought up on the midfield exploits of Callaghan, Souness, Kennedy and Molby. With a deftness of touch that delighted the eye and a rare command of a dead ball, his mastery of the centre of the park was at odds with many of his more rugged contemporaries.

At Leeds, McAllister was an integral part of one of the most effective, though also one of the most underrated midfield quartets of recent times. Dovetailing smoothly with Strachan, Speed and Batty, he spearheaded an unlikely title triumph, a triumph made all the more remarkable when you consider that the focal point of the Leeds attack, Lee Chapman, possessed all the mobility and dynamism of a heavily sedated hippo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6-bc0wWMNT0

McAllister, all quick passes and incessant probing, stood out. He was a leader, a thinker, a player of variety and impact. He was the player Liverpool were crying out for in the summer of 1992. Instead, they brought in Paul Stewart. Yes. I know.

When he joined Coventry, aged 31, it seemed as if McAllister‘s career at the highest level was winding down. A perennial relegation struggle was all that appeared to beckon. But his dedication and craft shone through. Rather than slip quietly into retirement, Gary Mac rediscovered his mojo. In his fourth season at Highfield Road he struck 11 league goals, a significant tally for an ageing playmaker.

And he caught the eye of Gerard Houllier.

When Gary McAllister finally joined Liverpool, in the summer of 2000, he was 35 years and six months old. Older, incidentally, than the Steven Gerrard who bid Anfield an emotional farewell in May. Despite his Coventry renaissance, it was a transfer that bemused as much as it delighted. As a general rule, Liverpool didn’t deal in has-beens.

Given that the average age of the team that finished the previous season was under 25, there was a definite logic to the signing. The likes of Gerrard, Heskey, Owen and Carragher had broken through at an early age but were each still to reach 23; Fowler, the longest serving member of the squad, had just turned 25. If nothing else, McAllister would provide some much-needed know-how and experience. And, if we were lucky, we thought we might get a few decent corners out of him. Expectations did not exactly scrape the sky.

But then, if history teaches us anything it’s that football supporters, me, you, all of us, are idiots. Big fat stupidhead idiots. Idiots consumed with the unswaying certainty of our opinions. Gary McAllister, like many many others, before and since, stands as testament to our glorious idiocy. For that alone, we should build a massive statue of him on Walton Breck Road beneath a neon sign endlessly flashing the words, “Think On…”

In fairness, his Anfield career took a while to take off. An unwarranted red card at Arsenal in the second game of the 2000/01 season was followed by two months out of the first team. It wasn’t until the second half of the campaign that McAllister began to show the Liverpool crowd what he could do. And then, in the second half of the second half of the campaign, he made himself a legend.

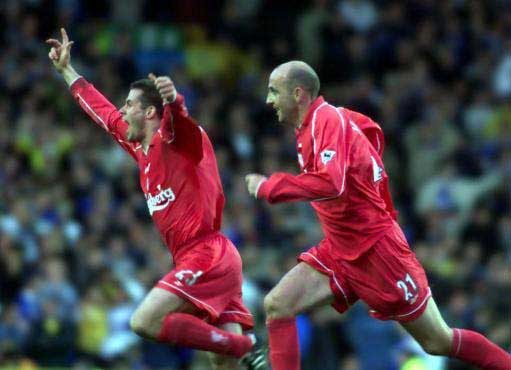

It started, in thrillingly chaotic fashion, at Goodison. A free kick. Four minutes into injury time. 44 yards from the Everton goal. We all know what happened — the glance, the instant weighing up of possibilities, the conviction, the execution, the explosion, the unbridled joy. What is seldom mentioned is the context. Liverpool had won just one of the previous eight league games. A draw would have left them eight points away from a Champions League place with six matches remaining. McAllister’s act of improvisation propelled the whole club onwards, fostering the belief and momentum that brought the season to an historic end.

It started, in thrillingly chaotic fashion, at Goodison. A free kick. Four minutes into injury time. 44 yards from the Everton goal. We all know what happened — the glance, the instant weighing up of possibilities, the conviction, the execution, the explosion, the unbridled joy. What is seldom mentioned is the context. Liverpool had won just one of the previous eight league games. A draw would have left them eight points away from a Champions League place with six matches remaining. McAllister’s act of improvisation propelled the whole club onwards, fostering the belief and momentum that brought the season to an historic end.

Three days later, he scored the penalty that defeated Barcelona at Anfield, to secure a place in the UEFA Cup Final. Another three days on, another vital spot kick, this time to defeat Tottenham. A stunning free kick against Coventry. The same at Bradford. Five goals in five games. Showing the way, pushing on, always pushing, pushing to a hat-trick of cup wins and the all-important Champions League berth.

And then in Dortmund he pushed further. A penalty buried, a sharp through ball for Fowler to dispatch, a free kick that invited Babbel to head home, and the decisive moment deep in extra time, a vicious, in-swinging dead ball that skimmed the head of defender, Geli, before nestling in the Alaves net. Man-of the-match in a European final at the age of 36. That’s some going.

Perhaps inevitably, his impact waned during the following season. But that didn’t matter. He’d done enough. He remained a hugely influential figure at the club, a mentor for Steven Gerrard and a symbol of the professionalism others should aspire to.

Gary McAllister left Anfield with a load of medals, a load of memories and the gratitude of all who saw him play. He came in as a curiosity, a question mark, a raised eyebrow. But he departed as a Liverpool player. A proper Liverpool player.

Maybe it’s what he’d always been. It just took us a while to realise.

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: PA Images/David Rawcliffe-Propaganda Photo

Like The Anfield Wrap on Facebook

Subscribe to TAW Player: https://www.theanfieldwrap.com/player/subscribe

Good read that, Neil. Before I’d even cottoned on to it being 15 years since he’d signed I had a weirdly vivid dream earlier this week that I was playing tennis and Gary Mac was my doubles partner. I couldn’t stop hitting the net and he looked dead disappointed in me. No earthly idea why I’m sharing this; just thought it was mad and I can’t sleep cos it’s too hot.