THE gleeful face of Kenny Dalglish in the Anfield stands at the weekend was a reminder of a time so long ago now, it seems like another place – a different world.

In so many ways it was.

When that same face beamed with joy 29 years ago, there was no stand at Anfield named after the great man. Neither was there a Centenary Stand.

Then, it was just the plain old single-tiered Kemlyn Road. The Main Stand was the old Main Stand. And The Spion Kop was still a terrace.

The Anfield Road end didn’t have a second tier, and the bronze Bill Shankly that now greets visitors from Walton Breck Road didn’t exist.

No one had heard of Mighty Red, Tom Hicks, George Gillett or of kits made by Warrior.

It was Liverpool Football Club. But not as we know it now.

Goalkeepers, including ours, Bruce Grobbelaar, could pick up a backpass, and did so with monotonous regularity. Midfielders, including ours, especially Steve McMahon, could put in a tackle worthy of the name.

A drinking culture was rife among players of the era. And, if you were Steve Nicol, a crisp-eating culture, too.

The cheapest tickets at Anfield were just £4 and Liverpool won things regularly. Including the title.

That was how it was on April 28, 1990. If you could somehow go back to that time now, no one would believe that, 29 years later, The Reds would still be waiting, hoping and praying for title number 19.

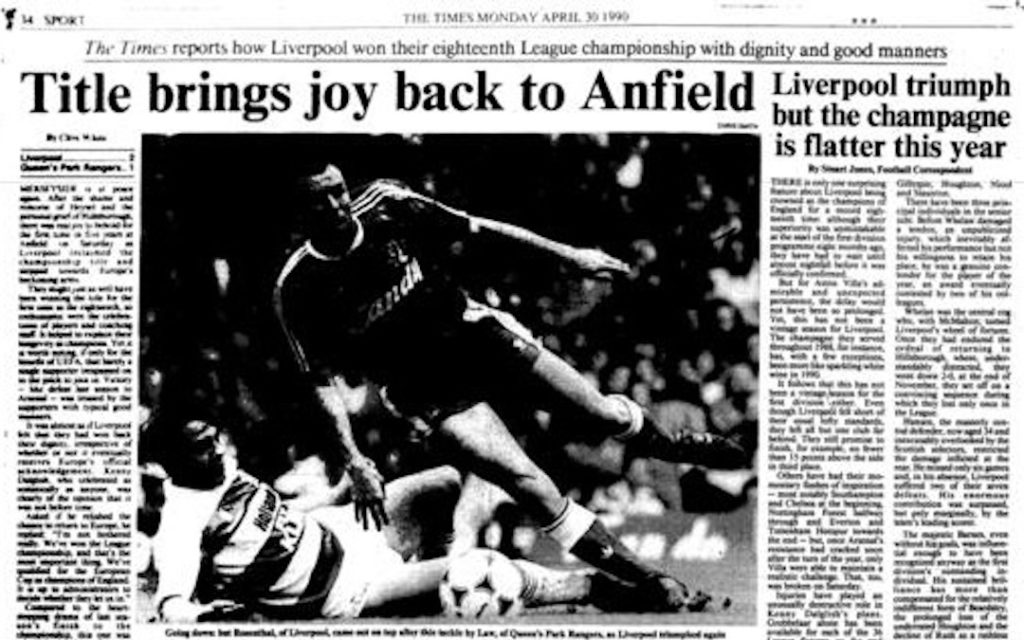

The Liverpool Echo from the Monday after the Saturday before when Dalglish’s side had clinched the title with a 2-1 win over Queens Park Rangers described Liverpool as “Untouchables” and featured quotes from Jan Molby in a 12-page pullout.

“Football is unpredictable,” the Danish midfielder said. “The only thing you can predict is that Liverpool will always be there or thereabouts when the honours are being handed out.”

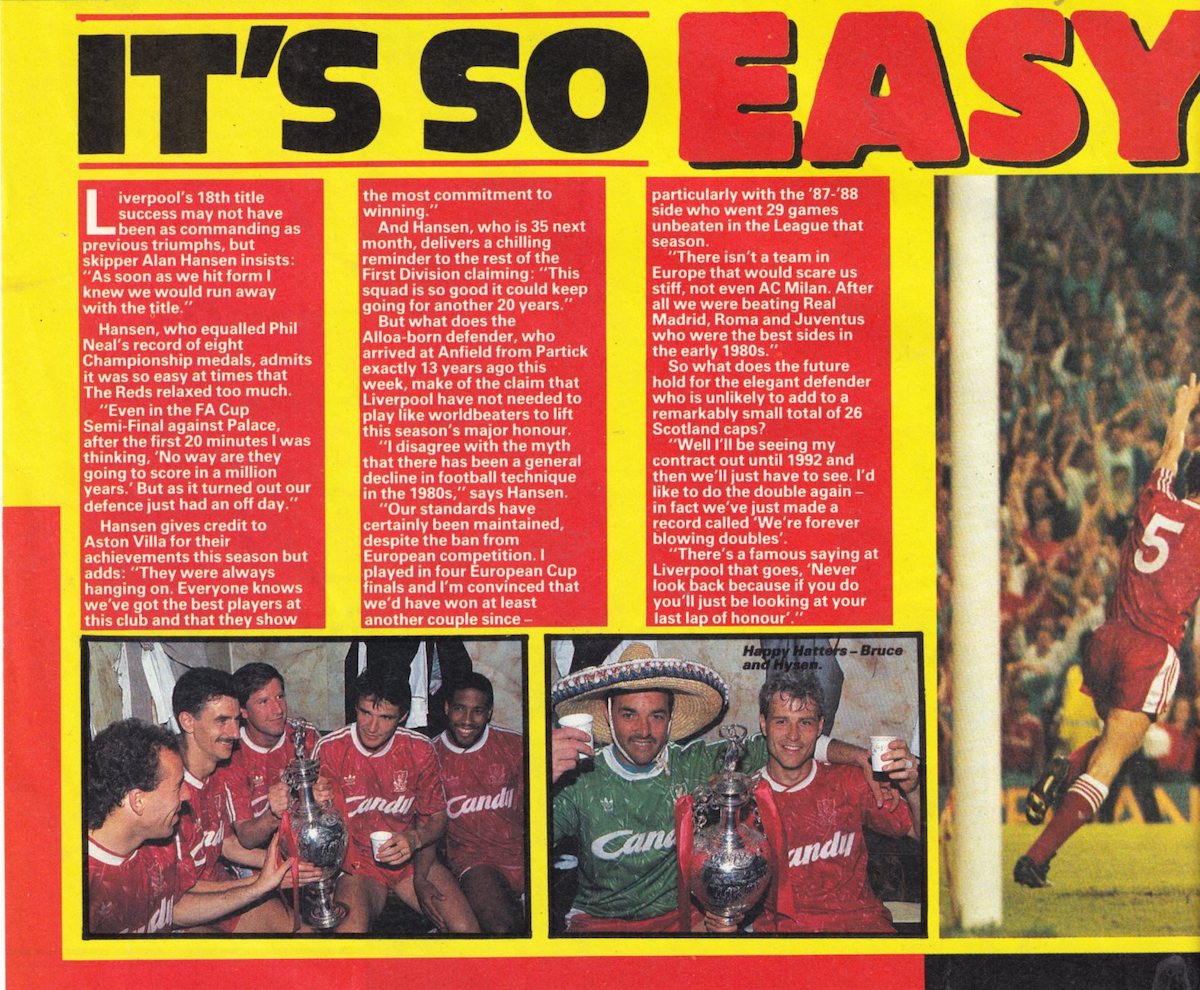

“Some people might wonder if we get fed up winning things here,” Molby added. “They should just look at Alan Hansen. He has won medals in the 70s, 80s, and now in the 90s and he’s still loving every minute.”

The match analysis from former Echo sports editor Ken Rogers began: “Isn’t it about time that the League Championship trophy was melted down and re-cast in the shape of a glittering Liver Bird?”

Hansen’s eighth title, at the age of 34, was Liverpool’s 10th in 15 years. It was taken a little for granted back then.

Now the 63-year-old Hansen must wonder, like the rest of us, how the honours board at Anfield still reads 18 titles almost three decades on.

Molby, sadly, wasn’t quite as accurate with his predictions as his passing.

The 29 years that have followed have yielded just four runners-up places in the league. What was once Liverpool’s bread and butter became a main course The Reds could never quite manage, leaving it free for others to feast on.

There have been three FA Cups, four League Cups, a UEFA Cup and the big one, The European Cup in 2005, since league title silverware last troubled the insides of the Anfield trophy cabinets.

There has also been much mediocrity. A trio of eighth-placed finishes, another three times seventh, another four times sixth.

The 37,758 present at Anfield to witness Dalglish and Ronnie Moran prematurely pogoing together while their main rivals for the title, Aston Villa, continued to play against Norwich City may have included the moaners that had peppered the pages of The Football Echo just days before.

But, nevertheless, while many questioned Liverpool’s last title-winning side, few would have foresaw the fallow years that followed.

Despite boasting statistically the best defence in the league – 37 goals conceded in 38 games – concerns about the back four filled the local letters pages just days before title 18 was lifted. This was how supporters aired their gripes then. The printed word. Papers and fanzines.

ALL CHANGE: The standing Kop and the Kemlyn Road

Pre forums, pre Twitter, pre podcasts, pre YouTube. Pre internet.

A 4-3 FA Cup semi-final defeat to Crystal Palace, a side torn apart 9-0 at Anfield earlier in the season, was still raw for many.

Alan Davies from Kirkby wrote: “As a mad Liverpudlian who has hardly missed a match since seeing them come up to Division One in 1962, I’d just like to say that the current Liverpool defence is the shakiest in that time.

“Alan Hansen, although superb, can’t go on forever and has always been vulnerable to the high ball. Glenn Hysen can head a ball, but unfortunately heads it anywhere. And the two full backs just aren’t up to standard.”

Another Alan, Mr Easson, from Woolton, bemoaned The Reds’ set-piece defending, claimed a lack of goals from midfield was holding Liverpool back and even took a swipe at the quality of the division at the time.

Liverpool ultimately finished the season nine points clear of nearest challengers Villa, on 79 to their 70, with five defeats to their name.

Villa lost 10 times that season, third-placed Spurs 13 and Arsenal, champions the previous season in the most dramatic of finales at Anfield, were back in fourth having lost 12 times.

Manchester United, who had been on the verge of sacking Alex Ferguson earlier in the season finished 13th with the Manchester City of old a lowly 14th.

But while foes of the modern day were meandering, Liverpool’s defence was being questioned and one national journalist wrote of a championship-winning team “which has probably been paid greater respect by the opposition than it has been entitled to,” there was a factor missing from many of the pages that document that slog to silverware.

Hillsborough.

Dalglish later admitted his resignation as manager in 1991 was a year late. And in a time less tuned to the issues of mental health, it’s more than fair to assume both manager and players were suffering in silence.

“In the 22 months between Hillsborough and my resignation, the strain kept growing until I finally snapped,” Dalglish said in his autobiography.

John Aldridge, the club’s top goalscorer in 1988-89 who was allowed to depart for Real Sociedad a season on, later wrote of the effects of the disaster and the funerals that followed.

“The thought of training never entered my head,” Aldridge said.

“I remember trying to go jogging but I couldn’t run. There was a time when I wondered if I would ever muster the strength to play. I seriously considered retirement. I was learning about what was relevant in life.”

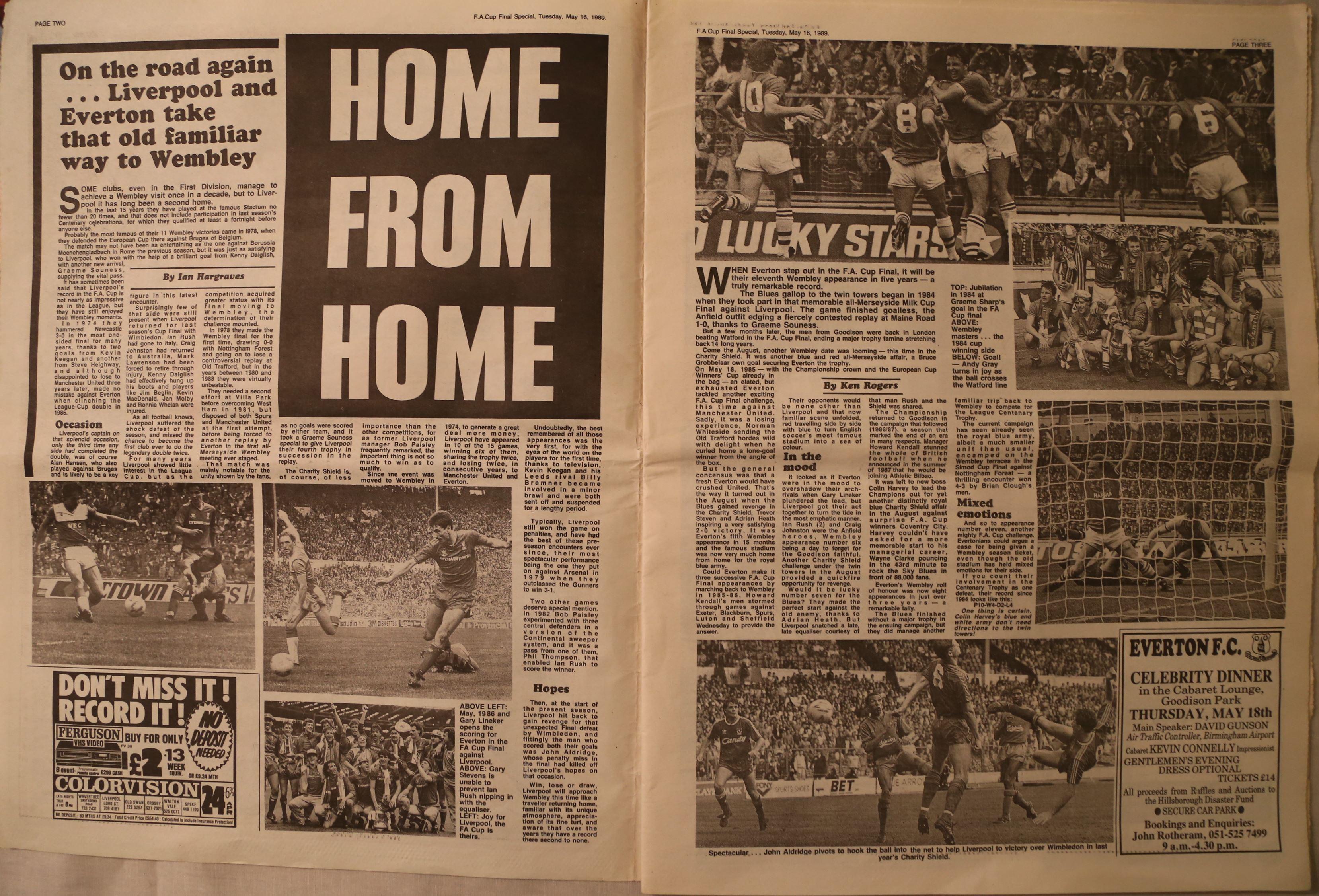

Yet play again they all did. Less than a month after Hillsborough fixtures resumed with a league match at Goodison Park. The semi final of the FA Cup was rearranged and played at Old Trafford. The Reds eventually won the cup, beating Everton at Wembley in the final in another emotionally charged afternoon.

Throw in that last-day league defeat to Arsenal at Anfield that handed The Gunners the title, and it was perhaps unsurprising that it took until April for Liverpool to win more than two league games in a row the following season.

They could play. But perhaps all wasn’t well. With the manager and with the players. And if not, who could blame them? Knowing what they knew, seeing what they had seen, hearing what they had heard. They had to carry on regardless. And expectations had not waned.

Five defeats in all competitions in October and November 1989 – including to Sheffield Wednesday at Hillsborough only seven months after the fateful cup semi final with Nottingham Forest – suggested the pressure to deliver was proving to be too much.

That Liverpool, inspired by Footballer of the Year John Barnes, who scored 22 league goals, recovered to only suffer one further defeat in the league that season from November onwards was perhaps warranting of more praise then given the circumstances.

It still is.

A year earlier, Dalglish attended so many funerals after Hillsborough that he needed a police escort so he could go to four in one day. He personally made sure the club was represented at every funeral. The players went, too.

They also visited fans in hospital. Some in comas. They consoled the bereaved. They saw grief first hand. Over and over.

Aldridge wrote in his autobiography: “I think people sometimes forget Hillsborough affected the players. Ray Houghton said the experience of visiting so many hospitals and attending so many funerals made him more upset than he’d ever been before.

“Alan Hansen, the Liverpool captain, was said to be visibly shaking at times. Bruce Grobbelaar had, like myself, considered retirement. Steve McMahon claimed the Hillsborough tragedy was a watershed in his life. ‘I grew up almost overnight,’ he said.

“Players openly wept in front of each other, which was incredible. There had never been such a display of emotion among the Liverpool players before. Usually we spent most of our time taking the mick out of each other, but Hillsborough pulled down the facade and showed us up for what we were: vulnerable human beings.”

In 2019, evidence of a macho culture around football remains. “Man up” still exists.

Mental health is discussed more but still not enough. Plenty inside the game say support is still scarce and often of a tick-box nature. Plenty on the outside still point to fame and fortune should a player speak out.

In 1990, it’s a fair bet to say help and understanding was close to non existent.

Yet a Liverpool team of young men present at the club’s darkest day, managed by a man who later admitted his own troubles sparked by Hillsborough, prevailed.

Dalglish was still in his 30s. He refused to speak about Hillsborough. He refused help. He never wanted it to be about him.

The FA Cup victory in 1989, and the league title that followed in 1990, should be remembered in that cruellest of context. What was displayed was an incredible force of will by an incredible set of people in unprecedented circumstances.

No title is easy. No championship win is simple. Liverpool know that to be true more than most, and that’s now the case for different reasons in a football landscape changed beyond all recognition from those days.

But title 18 was special, even if it wasn’t treated as such.

Ronny Rosenthal, whose timely contribution on loan yielded seven vital goals to help Liverpool over the line, said of the title celebrations: “We had some champagne and there was a bit of singing. But there was not a night of massive celebration.

“We had a meal with our families. Hey, we were expected to win. Had I known then that it was going to be Liverpool’s last title, I would have made more of it.”

Twenty-nine years on, Liverpool have a chance once again. You suspect the party will be different if what’s appeared impossible so many times finally plays out how we want it.

Should it happen, it won’t just be Ronny making more of it.

Kenny will be smiling once again.

For instant reaction to all the Liverpool news and events that matter to you, SUBSCRIBE to TAW Player…

“These are the most exciting times I’ve ever had as a Liverpool fan.

“I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else right now.” ✊

🗣 Subscribe to #TAWPlayer for all of our buildup, live from Porto, as The Reds’ look to make another European Cup semi final 👉 https://t.co/lmNtByMZeZ pic.twitter.com/2NOs7AcABz

— The Anfield Wrap (@TheAnfieldWrap) April 16, 2019

Recent Posts:

[rpfc_recent_posts_from_category meta=”true”]

Pics: David Rawcliffe-Propaganda Photo

One of if not the most poignant pieces about that time.

What a soulful reflection Gareth. Thank you.

On a purely footballing front, the 4-3 loss to Palace in that semi final is comfortably among my top five most traumatic defeats. And it seemed to set the template for a decade of defensive aerial woes as well.

Great piece this, Gareth. Beautifully done.

This is an excellent article. Post traumatic stress wasn’t even a thing back in the 80/90s, counselling was virtually non existent & anyone who said they needed help was considered over dramatic. Not everything has improved with time, but some things have.

Well put. I have been eventually diagnosed with PTSD as a result of Heysel and Hillsborough, only took until 2008. Even now people don’t understand it and I still suffer nightmares (not fun for the wife) and have knock on effects from it. Some of our players went through both occasions and the lies and shit that came out afterwards. Takes it toll eventually.

Well done Gareth, it puts many things in to perspective.

As for the in-between bits as to what happened, we had a fair bit of misfortune, some brought on us by appointing the wrong people to be ‘custodians’ (owners) as much as managers (don’t get me started on Souness or Hodgson years). You wonder what may have been had Houllier not had a heart attack, or we hadn’t had idiot owners when Rafa was at the helm… or better still, we waited for Dalglish to return after he stepped down and just had a caretaker in charge while he was given a sabbatical… His later return had it’s moments, however Charlie Adam, Stewart Downing and paying £35m for Andy Carroll weren’t such moments (that said, someone who claims he signed all the best players that Spurs had and the same for his time at Liverpool, makes claims these were his signings, probably explains why he hasn’t got a job at either club now and also explains why we don’t sign such expensive dross anymore.). Anyways, our last trophy was under Kenny and the last real glory, golden period came under Rafa… That is until now.

So Hillsborough as I keep saying was the thing that truly knocked us off our perch and not Fergie, we would have won the League in 89 if it wasn’t for that fatal day. Likewise we would have probably have won the European Cup in 85 if it wasn’t for Heysel.

Equally, we have had moments were we have been robbed by officials down the years from adding to the total. I could write an article all on its own on that one and that just about Sergio Ramos and last year’s CL Final.

We are now due some good fortune to go alongside our great team.

Good article.

Thanks Gareth, just brilliant.

Great piece of writing

Brilliant piece – spot on! YNWA

Great piece Robbo. I was barely 11 when we last won the league and still about a year away from my first trip to Anfield. Probably too young to appreciate the league win and certainly too young to understand the post-Hillsborough effect on the team.

Hi Gareth, that was a very nice article. Thanks for sharing that.

I was too young and far away from all you’ve described to comprehend the effects let alone feel it like you, yours and all those families, including the players experienced.

But it has certainly not diminished in importance in my mind and heart as a Reds supporter ever since that day.

Looking forward to the next game.